With the growth of a literate middle class and the greater availability and affordability of paper and printing, children’s literature came into its own in the mid-19th century, and here in Special Collections and University Archives, we hold many of examples of colorful, richly illustrated children’s literature from the late 19th / early 20th century.

Included within our holdings are at least two “movable books,” publications that enhanced young children’s reading experiences by allowing them, though the use of pull tabs, flaps, and other gimmicks, to simulate action. Among our holdings are at least two examples of movable books: a reprint of Ernest Nister’s Revolving Pictures (1892) and a 1979 reprint of The Doll’s House by Lothar Meggendorfer, considered the father of the pop-up book, a form that continues to be very popular today.

Though his books didn’t rely on movable parts, Peter Newell (1862-1924) was an innovator in creating novelties that appealed to young readers. The rare book collection includes two unusual books published by Newell. In both The Shadow Show and The Hole Book, as well as his other works, Newell manipulated the book form to help tell his stories.

Peter Newel (frontispiece from Through the Looking-Glass (1901))

Peter S. H. Newell (1862-1924) was born to a family of farmers in Illinois. He studied at the Art Students’ League and by the time he was in his mid-twenties had become a popular illustrator for various periodicals, his work regularly appearing in such publications as Harper’s Weekly, Scribner’s Magazine, and The Saturday Evening Post. He was particularly noted for his imaginative caricatures, some of which would be regarded today as racially insensitive.

In The Hole Book (1908), also one of Newell’s more popular works, the story follows the path of an errant bullet as it causes mayhem through a neighborhood. The story’s inventiveness is found in Newell’s imaginative use of an actual small, round hole that pierces each successive illustration in the book.

A sample illustration and rhyme from The Hole Book

Similarly, The Slant Book (1910) tells the story of a runaway baby carriage, with the story being enhanced by the book’s shape, which, instead of the usual rectangle, is a slanted rhomboid. (Newman Library holds a 1966 reprint of The Slant Book in its circulating collection.) Newell’s idea for The Slant Book led him to file a patent claim, in which he wrote, “In books made according to my invention the shape of the book itself and of the pages therein suggests the action or motion in which is intended to characterize the illustration contained therein.” Newell was granted patent 970,943 on September 20, 1910. It was one of several patents granted to Newell for book and toy designs.

Newell’s A Shadow Show (1896) relies on the translucency of paper for its gimmick. Rather than telling a story, the book simply presents a series of rather oddly contrived colored illustrations. When the reader flips the page, the previous page’s illustration appears in silhouette, revealing a much different subject. Unfortunately, the copy in the rare book collection has not held up well over time, and the illustrations have all transferred to adjacent pages, making the silhouettes difficult to distinguish.

A sample from A Shadow Show (Due to the condition of the original, this digital copy has been altered for illustrative purposes.)

Newell is perhaps best remembered for his first book, Topsys and Turvys (1893) and its two sequels. In the Topsys and Turvys series, each page contains an illustration and accompanying first line of a rhyming couplet as a caption. When the page is inverted, a much different illustration is revealed, and the caption appearing below the flipped image completes the rhyming couplet, explaining the illustration. Illustrations from these books continue to be frequently used as examples of optical illusions. A digitized version of The first Topsys and Turvys book may be found on the Library of Congress website.

In addition to providing illustrations for popular magazines and publishing his own books, Newell also illustrated the works of other authors of children’s literature, chief among them, perhaps, being his illustrated edition of Through the Looking-Glass (1901), which also may be found in the rare books collection. Later, Newell tried his hand at comic strip illustration. For 18 months in 1906/1907, Newell’s “The Naps of Polly Sleepyhead” appeared among such acknowledged comic strip pioneers as “Buster Brown” and “Little Nemo in Slumberland.” A second strip, “Wishing Willy,” wasn’t so successful and lasted through only six installments in 1913.

I’d planned here to provide the briefest of overviews on our holdings in children’s literature but instead got sidetracked by this Peter Newell tangent. Suffice it to say, the few books mentioned here comprise just the smallest part our children’s literature holdings, many of which overlap with our collection focus areas in the history of food and drink, the Civil War, local and regional history, etc. Together, these works can provide a different perspective on their subject matter or be used to examine popular culture and early childhood education in earlier eras. Or they can can simply be enjoyed for what they were intended: fun reading for the young and young at heart.

Mourn, O Venuses and Cupids

Mourn, O Venuses and Cupids

Over the past few months, I’ve stepped outside my normal topical areas of social justice and the history of traditionally marginalized communities. This departure was related to an exhibit titled Flora Virginica that is on display in our reading room from February 5, through March 16. I enjoy putting together exhibits, so I was happy to take this on even though it was something I knew nothing about. This blog post will include a description of the exhibit, the reasons for its existence, and the interesting history I discovered while putting it together (only not in that order). Enjoy!

Over the past few months, I’ve stepped outside my normal topical areas of social justice and the history of traditionally marginalized communities. This departure was related to an exhibit titled Flora Virginica that is on display in our reading room from February 5, through March 16. I enjoy putting together exhibits, so I was happy to take this on even though it was something I knew nothing about. This blog post will include a description of the exhibit, the reasons for its existence, and the interesting history I discovered while putting it together (only not in that order). Enjoy!

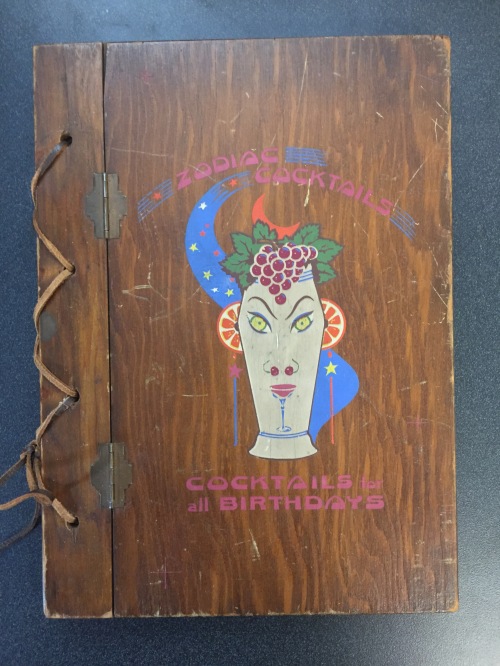

First, a little bit about wood book covers in general. If you take a moment and do a quick Internet search (I’ll wait…), you will likely discover that there are hundreds upon hundreds of sites providing instructions on how to make your own wood book cover. Wood has been a popular material for electronics cases and other applications for a few years now (I’ve personally watched as the number of products in this space has increased exponentially). Not surprisingly, this is a phenomenon that falls squarely into the category “everything old is new again”. The covers from our rare books collection are not freshly made. They mostly hail from the late 1930’s (one is on a book from the 1970’s – another period where wood was exceedingly popular on everything from cars to walls).

First, a little bit about wood book covers in general. If you take a moment and do a quick Internet search (I’ll wait…), you will likely discover that there are hundreds upon hundreds of sites providing instructions on how to make your own wood book cover. Wood has been a popular material for electronics cases and other applications for a few years now (I’ve personally watched as the number of products in this space has increased exponentially). Not surprisingly, this is a phenomenon that falls squarely into the category “everything old is new again”. The covers from our rare books collection are not freshly made. They mostly hail from the late 1930’s (one is on a book from the 1970’s – another period where wood was exceedingly popular on everything from cars to walls).  Our first two examples both focus on Southern style cuisine. They also rely on the Jim Crow mammie caricature. The introduction from the 1930’s volume reads “The very name ‘Southern Cookery’ seems to conjure up the vision of the old mammy, head tied with a red bandanna, a jovial, stoutish, wholesome personage . . .”

Our first two examples both focus on Southern style cuisine. They also rely on the Jim Crow mammie caricature. The introduction from the 1930’s volume reads “The very name ‘Southern Cookery’ seems to conjure up the vision of the old mammy, head tied with a red bandanna, a jovial, stoutish, wholesome personage . . .”

The content of this volume is as it would be with any book of cocktail recipes: useful in making cocktails. Still, it’s hard to take the author seriously in his attempt to “. . . demonstrate that people born under one sign of the zodiac are capable of drinking one or more combinations of liquor without ill-effect, whereas other combinations bring less pleasing results.” He has formulated a cocktail for each sign that he believes is the ideal cocktail for anyone born under that sign. Since we are currently under Sagittarius, I share with you the ideal cocktail for that sign:

The content of this volume is as it would be with any book of cocktail recipes: useful in making cocktails. Still, it’s hard to take the author seriously in his attempt to “. . . demonstrate that people born under one sign of the zodiac are capable of drinking one or more combinations of liquor without ill-effect, whereas other combinations bring less pleasing results.” He has formulated a cocktail for each sign that he believes is the ideal cocktail for anyone born under that sign. Since we are currently under Sagittarius, I share with you the ideal cocktail for that sign: The next item from 1939 will tell you your Bar-o-scope. This one is definitely not taking itself too seriously. It is described as:

The next item from 1939 will tell you your Bar-o-scope. This one is definitely not taking itself too seriously. It is described as:

Finally, there is a glorious metal “bound” cookbook from Pillsbury (1933). Right in the heart of the Art Deco period, this book incorporates elements of that iconic style into a housewife’s reference book titled Balanced Recipes.

Finally, there is a glorious metal “bound” cookbook from Pillsbury (1933). Right in the heart of the Art Deco period, this book incorporates elements of that iconic style into a housewife’s reference book titled Balanced Recipes.