Recently, I’ve been working on identifying artifacts and university memorabilia in our collections, and I came across a beautiful, four-stringed tenor banjo and its case. I did not anticipate that an item so innocuous as a musical instrument would lead down a path into learning about the university’s racist past, including minstrelsy and blackface.

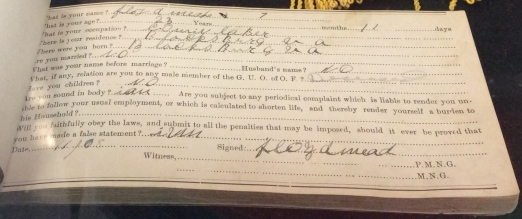

To start, I could find no information about the banjo’s former owner, so I investigated the banjo and case themselves for clues. Handwritten on the banjo head is “The Collegians, VPI, Blacksburg, VA.”, and the peghead identifies it as a Bruno banjo. Handwritten on the banjo’s case are the initials, “L.A.H.”

Searching through names related to our collections, I found the Lewis A. Hall Papers, Ms1983-009, very promising given his initials and his connection to Virginia Tech. Looking thru the collection, my excitement rose almost immediately when I found a reference to the Collegians – the band the banjo is advertising – in the printed items. Then I opened the folders of photographs and found a beautiful picture of the Collegians themselves, with one man holding this very banjo! A portrait in the collection is of Hall, and it’s clear he’s the same man holding the banjo.

Interested in finding out who else is in the photo, I pulled the Collegians folder in the Historical Photographs Collection. I found a copy of the same photo, dated 1923-1924, identifying the musicians from left: Robert B. Skinner (drummer); J.B. “Yash” Cole (trombone); Arthur Scrivenor Jr. (piano); Lewis A. Hall (banjo, manager, and director); H. Gaines Goodwin (saxophone); Bill Harmon (saxophone); and S.C. Wilson (trumpet, not pictured). This picture is also used in the 1924 Bugle yearbook.

There were two other pictures in the folder of Hall and the Collegians, dated 1922-1923, from left: L.A. “Lukie” Hall (tenor banjo); J.B. Cole (trumbone); R.S. “Bob” Skinner (traps); W. “Bass” Perkins (clarinet, violin, leader); Tom S. Rice (piano); W.D. “Willie” Harmon (saxophone); F.R. “Piggy” Hogg (saxophone, traps, manager); and S.C. “Stanley” Wilson (trumpet, not pictured).

After discovering the owner’s name, I wanted to know a bit more about both Hall and the Collegians. To the latter first – A dance orchestra at VPI formed in 1918 as the Southern Syncopating Saxophone Six. They were later renamed Virginia Tech Jazz Orchestra and known as the College Six. In 1922, they became the Collegians, and in 1931, they finally became the Southern Colonels. Today, the jazz band continues to perform, as part of the Corps of Cadets Regimental Band, the Highty-Tighties.

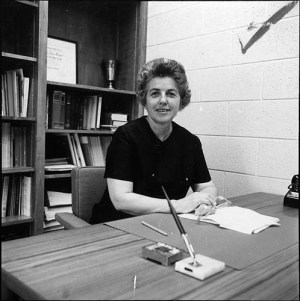

Second, Lewis Augustus Hall was born Lewis Augustus Hall in 1903 in Norfolk, Virginia. He attended VPI from 1920 to 1924. In addition to playing for the Collegians (also called the Tech Orchestra), he was a member of the Norfolk Club, Cotillion Club, Tennis Squad, the American Society of Mechanical Engineering, and the Virginia Tech Minstrels (more on this below). He also served as athletic editor for The Virginia Tech, the predecessor of the Collegiate Times, assistant manager of basketball, and manager of the freshman basketball team. Finally, he rose thru the ranks of the Corps of Cadets, graduating as Lieutenant of Company F. In 1924, he graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering. Upon graduation, Hall joined the Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Company, retiring as assistant vice-president in 1968. He married and with his wife Virginia had two sons. Hall maintained a connection to Virginia Tech, serving on the board of directors for the Virginia Tech Alumni Association for 15 years and earning the Alumni Distinguished Service Award in 1977. He died in 1982.

As mentioned above, Hall performed in the student club, the Virginia Tech Minstrels. I’ve heard of minstrel shows before and knew that students at Virginia Tech had held them. But this was my first time coming across them inadvertently, so it was a shock to learn that the owner of this banjo was a member of a minstrelsy.

If you aren’t aware, minstrel shows in the United States were a performance typically including skits, jokes, and music – predominantly performed by white people in blackface as a spoof, full of stereotypes and racist depictions, of Black people and their cultures. The 1924 Bugle (pp. 346-347) discusses the group and even depicts members in blackface. The Collegians are also listed as the group’s orchestra and a photo of the group includes Hall holding the banjo.

Hall’s and the Collegian’s involvement in minstrelsy shows that even an item as seemingly innocuous as a musical instrument can shed light on a part of our history that we – especially those of us in positions of privilege – do not always acknowledge. Yet, minstrel shows at Virginia Tech continued well into the 1960s, and this form of racism (and others) continues in America into the present day.

After Hollins College recently addressed controversy of blackface depictions in their yearbooks, Virginia Tech released the University Statement on Offensive Photographs to address the racist imagery in our past, and the University Libraries prepared a statement for our digital yearbook repositories to affirm our commitment to the Principles of Community and providing historical documentation to researchers.

My research about a mystery banjo took me down a path I could not imagine. I was at first excited to discover the owner’s identity, then horrified to learn about his and the instrument’s connection to racist entertainment. But in the end, the journey led me to learn more about this form of racism and how its legacy continues to impact American society. As the University statement says, “The history of our nation and the Commonwealth of Virginia has a common storyline starting with slavery and segregation, and moving toward our ultimate goal of treating everyone with respect and cherishing the strength that comes from diversity of identities and lived experiences. We, as a society, are somewhere in the middle of this process.”

For more information about blackface and minstrelsy, please read “Blackface: The Birth of an American Stereotype” from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History & Culture blog, A People’s Journey, A Nation’s Story, as well as Vox’s interview with author John Strausbaugh, “The complicated, always racist history of blackface” by Sean Illing.

(This post was edited May 22, 2019, with additional information about blackface and minstrelsy, the statements on offensive imagery in the Bugle yearbooks, and a revised title.)