Robert Burns Escaped from the Georgia Chain Gangs, Then Strove to Abolish Them

Here in Special Collections, we hold a number of books that have altered the course of history. Such works as Uncle Tom’s Cabin, The Communist Manifesto, Common Sense, and Walden have all profoundly shaped human thought and history, and all have places on our shelves.

Today, I want to tell you about another book in our collection that—though not as celebrated as the above examples—has had a significant influence on the course of events. Robert Elliott Burns’s I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang! is an account of the author’s experiences in—and escape from—the Georgia penal system of the 1920s. Burns’s vivid description of the system’s brutality and inhumanity has been credited with spurring 20th-century penal reforms in Georgia and beyond.

A New York City accountant, Burns volunteered for the army when the United States entered World War I. Assigned to a medical detachment with the 14th Railway Engineers, he served mostly at the front from September 1917, until armistice 14 months later. His service took its toll, and, according to his brother, Robert Burns returned home “nervously unstrung and mentally erratic—a typical shell-shock case.” In more recent years, Burns might have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Returning to New York, Burns struggled to rebuild his life, expecting that his military training and service would be valued by potential employers. He soon found, however, that his status as a veteran instead proved a handicap in securing employment. Burns arrived at the same conclusion as many veterans returning from that war and others.

The promises of the Y. M. C. A. secretaries and all the other “fountain-pen soldiers” who promised us so much in the name of the nation and the Government [sic] just before we’d go into action turned out to be the bunk. Just a lot of plain applesauce! Really an ex-soldier with A. E. F. [Amy Expeditionary Forces] service was looked upon as a sucker. The wise guys stayed home—landed the good jobs—or grew rich on war contracts … I went through hell for my country and my reward was the loss of my sweetheart and my position.

Disillusioned, Burns drifted from town to town as a vagrant, alighting in Atlanta in 1922. There, he participated in an armed robbery with two other men. Burns paints himself as a reluctant accomplice in the crime, coerced by the ringleader’s trickery and intimidation. The robbery netted the perpetrators a mere $5.80, and the three were captured 20 minutes afterward.

For his part in the theft, Burns was sentenced to six to ten years at hard labor. Expecting to serve his time in a penitentiary, Burns instead found himself designated for roadwork on a county chain gang. Issued a convict’s striped uniform and shackled with heavy chains, Burns was transported to one of Georgia’s many county prison camps.

Burns describes the Campbell County prison camp as filthy and dehumanizing. The endless days were filled with backbreaking and mind-numbing work; frequent beatings by guards; and subsistence-level, sometimes putrid food. The system made no pretense of reformation but instead sought to inflict harsh punishment and exploit a captive workforce.

One was never allowed to rest a moment but must always be hard at work, and even moving in the mass of chain was painful and tiring—yet if one did not keep up his work greater terrors and more brutal punishment was in reserve. If a convict wanted to stop for a second to wipe the sweat off his face, he would have to call out “Wiping if off” and wait until the guard replied, “Wipe it off” before he could do so.

Dinner came in a galvanized iron bucket …The contents of the iron bucket was boiled, dried cowpeas (not eaten anywhere else but in Georgia) and called “Red beans.” They were unpalatable, full of sand and worms.

Determining that he’d be unable to serve out his time in such conditions, Burns escaped the chain gang after several months. Evading his pursuers, the fugitive made his way to Chicago and arrived there with 60 cents in his pocket. He soon secured employment and began saving money. By 1925, Burns had saved enough to begin publishing The Greater Chicago Magazine, and he became a well-known figure about the city. During his rise to prominence, Burns claims, he was compelled by extortion into an unwanted marriage. Soon after he initiated divorce proceedings in 1929, Burns was arrested as a fugitive—betrayed, he asserts, by his estranged wife.

Citing the law-abiding and productive life that Burns had led in the seven years since his escape, a number of prominent Chicagoans helped Burns fight extradition. Assurances of leniency from Georgia authorities, however, persuaded Burns to voluntarily return. Upon arriving in Georgia, Burns found that the promises of fair treatment soon evaporated. Relegated to Troup County’s prison camp, Burns experienced conditions that were even more primitive and cruel than those he had experienced in Campbell County several years earlier.

After 14 months, Burns made a second escape, and he provides the reader with a step-by-step description of his flight. A natural-born storyteller, Burns keeps the reader in suspense through several close calls and daring risks.

Burns made his way to New Jersey, but, with the nation in the throes of the Great Depression, the success that he’d found in Chicago during the 1920s would elude him. Working at a series of menial jobs and living under an assumed identity, he decided to write a scathing indictment against the penal system from which he’d escaped. “It’s now my life’s ambition to destroy the chain-gang system in Georgia,” he told a friend, “and see substituted in its place a more humane and enlightened system of correction.”

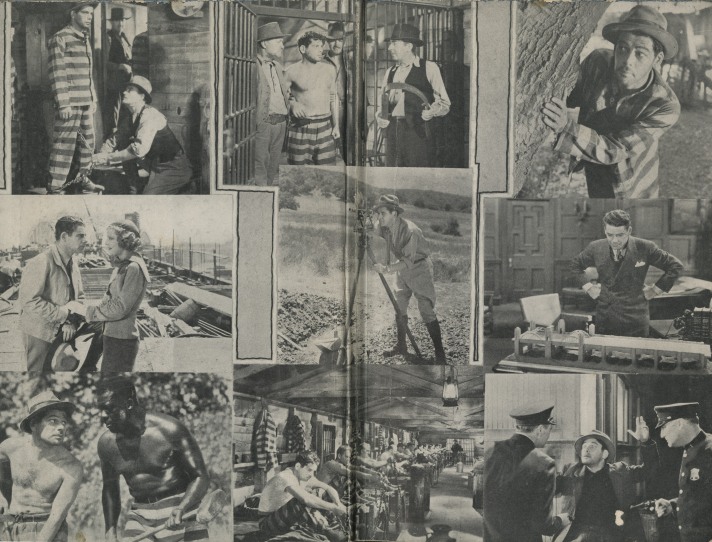

Serialized in True Detective Mysteries magazine in 1931, the fugitive’s story gained national attention. I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang! was later released in book form and became a bestseller. A popular film adaptation, I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, soon followed, netting three Academy Award nominations, including Best Actor for leading man Paul Muni and Best Picture.

In 1932, Burns was again arrested as a fugitive, but public outcry convinced New Jersey Governor A. Harry Moore to refuse extradition to Georgia, and Burns was soon released. In 1945, Burns again voluntarily returned to Georgia and appeared before the parole board, with no less a figure than Georgia Governor Ellis Arnall serving as his counsel. The board commuted Burns’s sentence to time served.

Burns died ten years later, but he lived long enough to witness reforms to the cruel system he opposed. The state of Georgia, spurred perhaps not so much by humanitarianism as by embarrassment, implemented a series of penal reforms in the 1940s. In abolishing the use of chain gangs within the state, Governor Arnall cited Burns’s story as the impetus behind his actions. Though chain gang systems remained in place in other Southern states, their abolition in Georgia signaled the beginning of an incremental change that would accelerate during the civil rights movement.

In Robert Burns, the chain gang system had perhaps created its own worst enemy: an inmate with the background, eloquence, and determination to attack it. His book caused widespread outrage and sparked condemnation of the chain gang system. It is impossible to gauge the influence of I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang! within the context of a wider movement for prison reform, and the book certainly didn’t cause the immediate demise of the chain gang system, but it undoubtedly implanted the need for reform in the national consciousness.

In addition to Burns’s book here in Special Collections, the library also holds the film’s screenplay and a videocassette copy of the film.